When Migrants Carry Scars. Female Genital Mutilation In Europe

|

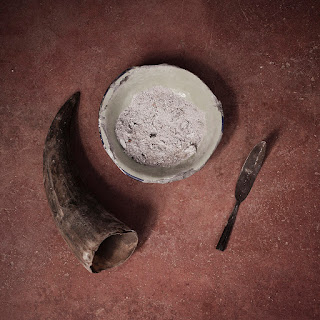

| Photo Simona Ghizzoni |

According to a new British law, any teacher, doctor, nurse or social care professional who comes across a case of a girl who has undergone genital mutilation has the duty to report it to the police.

This law, which took effect on Oct. 31 and applies to any victim under the age of 18, can result in sanctions and job termination if a case is not reported. It is just the latest legislation passed in Europe to deal with the issue of female genital mutilation (FGM), a phenomenon that until recently was thought to be limited to faraway countries.

But as can be seen by the below interactive map, FGM is surprisingly widespread in Europe as well, amid migrant communities from Somalia, Eritrea, Nigeria, Senegal, Gambia, Egypt.

Actually, Europe has its own, fortunately brief, history of “the cut.” The first case of clitoridectomy was reported in 1825 by the medical journal The Lancet: In Berlin, the surgeon Karl Ferdinand von Gräfe believed it could be the perfect cure for the excessive masturbating of a 15-year-old girl. For decades, cutting female genitals was thought to heal hysteria and certain sexual deviations, even in France and England. Then scientific societies imposed a ban on the procedure, which soon fell into oblivion and seemed to have been eliminated once and for all in Europe.

Today, following decades of migratory waves, the problem has resurfaced with a different aspect, forcing European countries to confront a societal wound as complex to fight as it is to understand.

The first challenge is measuring the scope of the problem. The only official statistic about FGM in Europe is a registered increase in women asking for asylum who come from countries where FGM is practiced: from 18,110 in 2008 to more than 25,000 in 2013. According to the UN Refugee Agency, this is due to a rise in the number of women asylum seekers from Eritrea, Guinea, Egypt and Mali, where FGM prevalence is over 89%. On the map you can see how many women were granted asylum from 2008 to 2011: from 2,225 in Britain to 75 in Italy. The reasons for fleeing from their countries varied, but in 2011 more than 2,000 girls and women were escaping precisely the threat of being forced to undergo circumcision.

Apart from refugees, it is difficult to calculate exactly how many FGM victims are living in Europe: the available data of member States, as well as Norway and Switzerland, only supplies us with a rough estimate.

The European Parliament has long cited the estimate of 500,000 victims and some 180,000 girls at risk, “but we really don't know what's the source of these numbers,” notes Jurgita Pečiūrienė — from the European Institute for Gender Equality (EIGE) in Lithuania, author of the only two existing comprehensive European studies on the issue. “But our main problem was that statistics gathering methods vary in each member State,” points out the expert. “Some use immigration data and others use health registrations so it is impossible to compare the results, and therefore the figures remain approximate.”

At the request of the European Commission, the EIGE is now working to provide a method, already tested in Sweden, Ireland and Portugal, which starting in 2016 will allow all the member States to assess FGM prevalence with more precision.

In the meantime, even though the actual extent of the phenomenon is unknown, the EU continues to invest in projects to raise awareness of and limit the practice of FGM in Europe. In addition to allocating almost 10 million euros in 2009 for 26 programs against FGM in 15 countries throughout Africa and the Middle East, the European Commission has invested generous sums to study and stop the “foreign ritual” from being practiced inside our own borders.

Some 800,000 euros has recently been earmarked for a web platform that will train health care, social workers and legal professionals in nine countries. “But at a time of economic crisis, we should be able to understand where our resources are required most urgently,” says Els Leye, a senior expert on FGM at Ghent University in Belgium. “I get the impression that the issue of FGM is being exploited by politicians because they believe that by pointing fingers at ethnic minorities, they will strike a chord with the audience.”

A special program has been launched in the UK, which has the largest Somali community in Europe (approximately 103,000 people). Taking into consideration that in Somalia the FGM prevalence is 98%, and exploring other communities from countries at risk, the House of Commons estimates that there are 170,000 victims and 65,000 girls at risk of FGM in UK.

The spokesperson for the massive anti-FGM campaign sponsored by The Guardian, Fahma Mohamed, a student of Somali origin, demanded that the government alerts all schools in order to prevent the female migrant students from undergoing the torture of the cut during travels to their countries of origin. “It has taken us this long just to get people talking about it,” she says. “We don't care how long it takes to make people listen.”

Female genital mutilation is a taboo, clandestine by definition, and elusive to those carrying out surveys: Little girls are “fixed” by traditional circumcisers or during holidays abroad, “and migrant communities don't report cases due to their internal loyalty,” adds Els Leye. There was an uproar in Sweden in June 2014 when it was discovered that 60 girls originating from Africa and attending an elementary school in the city of Norrköping had been cut: One of them was taken to the emergency room due to lacerating menstrual cramps. Yet Sweden was the first country in Europe to be on the look-out for similar cases, having passed a law abolishing FGM as far back as 1982: Today it counts 42,000 victims and thousands of girls at risk of FGM.

France, the Netherlands, Italy, Spain and Portugal have invested resources to fight against the practice, as has Cyprus, where an estimated 1,500 victims reside, and Hungary which counts a maximum of 350 victims. A few member States have established a national database; Belgium is the only EU country to have developed a method for constant monitoring; France depends on police registers and data from the Public Prosecutor's offices, NGOs and a Department for FGM data collection begun in 2008; Portugal (even with only 43 victims) and Ireland gather data from hospitals.

“We have to study the migrant attitudes more deeply,” points out Leye, who is now involved in an international project on FGM in Belgium, France and Italy. “There are huge differences between ethnic groups in each African country. Furthermore, migration has a great influence on the practice of FGM, in two very opposite senses: Some groups abandon it because, living now in Europe, they don't feel the social pressure from their societies anymore; for others, genital mutilation becomes a mark of cultural identity, believed to preserve their daughters from customs considered “too Westener” or leading to promiscuousness.”

Despite the increase in anti-FGM legislation, cases that have actually made it to court are quite rare, with only about 60 convictions, 50 of which are in France alone.

Elsewhere, beyond the silence that envelops the cutting tradition, there are few social care professionals or doctors with enough knowledge or expertise to assist victims. In UK, for instance, a law criminalizing FGM was passed in 1985 and in the past five years the police have investigated 200 cases. Still, the only trial that has ever been held took place last February and ended with an acquittal: He was a doctor, accused of re-sewing up after childbirth a Somali woman who had been a victim of infibulation.

Elsewhere, beyond the silence that envelops the cutting tradition, there are few social care professionals or doctors with enough knowledge or expertise to assist victims. In UK, for instance, a law criminalizing FGM was passed in 1985 and in the past five years the police have investigated 200 cases. Still, the only trial that has ever been held took place last February and ended with an acquittal: He was a doctor, accused of re-sewing up after childbirth a Somali woman who had been a victim of infibulation.

On February 6, on the International Day of Zero Tolerance for Female Genital Mutilation, the European Commission will release the results of a new study into whether current national anti-FGM laws are effective enough in curbing ritual cutting. The findings may push authorities to look for whole new strategies to combat an inevitably complex problem, which includes such factors as gender inequality and migrant integration.

This report is part of the UNCUT project on female genital mutilations (FGM). Produced with the support of the “Innovation in Development Reporting Grant Program” of the European Journalism Centre (EJC), funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, and carried out in partnership with ActionAid NGO and the cultural association Zona.

From Worldcrunch, 2 December 2015

Commenti

Posta un commento